Suche

Neu

- Book Review: "Losing My Virginity" by Sir... (tra, 11.Jan.13)

- Movie Review: Carnage (tra, 11.Jan.13)

- Who will join Mitt Romney on the way to the... (tra, 26.Jul.12)

- The Cheesy-Grits Southern Strategy worked... (tra, 14.Mär.12)

- What the Spanish-American War can teach us... (tra, 11.Mär.12)

Links

Navigation

Meta

Archiv

- März 2012MoDiMiDoFrSaSo12345891012131516171819202122232425262728293031

RSS

What the Spanish-American War can teach us about KONY 2012

On February 15th, 1898 the USS Maine sunk. An explosion had ripped the ship apart, and there was no doubt who the evil-doers were: the Spanish. The cowardly Spanish, as the press would write.

As the main source of public information, Newspapers quickly set the tone of the conversation. And they did by pushing heavily for military action against the Spanish colonial power on Cuba.

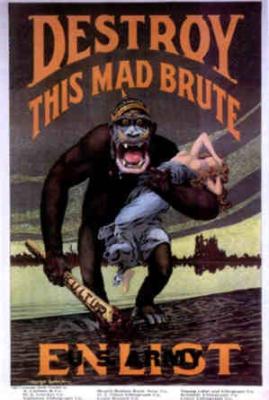

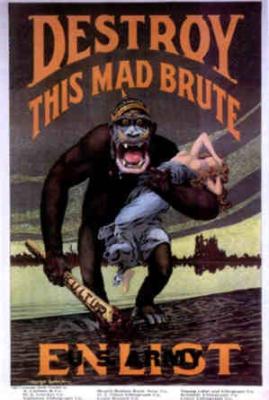

Newspapers cited old, oftentimes second- or third-hand information as truth; they painted lurid pictures of the horrors of life on Cuba under oppressive Spanish rule; there was talk of death camps, cannibalism, torture, and the noble Amazon Warriors fighting the oppression; they printed propaganda posters and plastered the streets.

Soon, most media outlets sent hundreds of reporters, artists, and photographers south to recount Spanish atrocities. Yet upon arrival they found little to report.

"There is no war," the famous journalist Remington wrote to his boss. He requested to return to America.

Remington's boss, William Randolph Hearst, sent a cable in reply: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war." Hearst was true to his word. For weeks after the USS Maine disaster, the Journal devoted more than eight pages of fabricated war stories a day. Not to be outdone, other papers followed Hearst's lead. Hundreds of editorials demanded that American honor be avenged. Most Americans believed what they read. Soon a rallying cry could be heard everywhere — in the papers, on the streets, and in the halls of Congress: "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain."

The propaganda had worked. The American people, and important figures of American politics – most notably one Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy – lobbied congress into a war. And through their disregard for responsible journalism, Newspapers had successfully advocated military action.

On April 25th, 1898 the US declared war on Spain, which in turn led to the American-Philippine War.

Fast-forward to 2012. A media outlet releases a movie calling for military action in Uganda. There is talk of child soldiers and sex slaves; there are pictures of mutilated victims. And the evil-doer is presented next to Adolf Hitler and Osama bin Laden: a man called Joseph Kony.

The call to action is similar: they present viewers with pictures and stories that cater to our emotions and our feeling of justice, rather than our sense of reason. On April 20th, the organizers call onto the world to litter the streets with posters calling for military action in Uganda; they start to mobilize important figures of public life into supporting the movement; and ultimately, they ask us to lobby the American congress into a war.

The Spanish-American war shows us that media propaganda can mobilize a whole population into demanding war. It also shows us that once military action is taken, it’s not a cut-and-dry issue; violence always begets violence.

Journalists on the ground are already warning us of this propaganda. Kony is not in Uganda anymore, and his power is fading. The facts in the movie are to a large extent six years old and over-exaggerated. The region is largely at peace, with problems of health care, poverty and political stability – not the tyranny of Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army – making the lives of Ugandans difficult.

A war is the last thing they want. And it is the last thing that we should want.

But what will we ultimately believe? Will we be lured into supporting war based on propaganda pictures catering to our emotions again?

We shall see.

As the main source of public information, Newspapers quickly set the tone of the conversation. And they did by pushing heavily for military action against the Spanish colonial power on Cuba.

Newspapers cited old, oftentimes second- or third-hand information as truth; they painted lurid pictures of the horrors of life on Cuba under oppressive Spanish rule; there was talk of death camps, cannibalism, torture, and the noble Amazon Warriors fighting the oppression; they printed propaganda posters and plastered the streets.

Soon, most media outlets sent hundreds of reporters, artists, and photographers south to recount Spanish atrocities. Yet upon arrival they found little to report.

"There is no war," the famous journalist Remington wrote to his boss. He requested to return to America.

Remington's boss, William Randolph Hearst, sent a cable in reply: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war." Hearst was true to his word. For weeks after the USS Maine disaster, the Journal devoted more than eight pages of fabricated war stories a day. Not to be outdone, other papers followed Hearst's lead. Hundreds of editorials demanded that American honor be avenged. Most Americans believed what they read. Soon a rallying cry could be heard everywhere — in the papers, on the streets, and in the halls of Congress: "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain."

The propaganda had worked. The American people, and important figures of American politics – most notably one Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy – lobbied congress into a war. And through their disregard for responsible journalism, Newspapers had successfully advocated military action.

On April 25th, 1898 the US declared war on Spain, which in turn led to the American-Philippine War.

Fast-forward to 2012. A media outlet releases a movie calling for military action in Uganda. There is talk of child soldiers and sex slaves; there are pictures of mutilated victims. And the evil-doer is presented next to Adolf Hitler and Osama bin Laden: a man called Joseph Kony.

The call to action is similar: they present viewers with pictures and stories that cater to our emotions and our feeling of justice, rather than our sense of reason. On April 20th, the organizers call onto the world to litter the streets with posters calling for military action in Uganda; they start to mobilize important figures of public life into supporting the movement; and ultimately, they ask us to lobby the American congress into a war.

The Spanish-American war shows us that media propaganda can mobilize a whole population into demanding war. It also shows us that once military action is taken, it’s not a cut-and-dry issue; violence always begets violence.

Journalists on the ground are already warning us of this propaganda. Kony is not in Uganda anymore, and his power is fading. The facts in the movie are to a large extent six years old and over-exaggerated. The region is largely at peace, with problems of health care, poverty and political stability – not the tyranny of Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army – making the lives of Ugandans difficult.

A war is the last thing they want. And it is the last thing that we should want.

But what will we ultimately believe? Will we be lured into supporting war based on propaganda pictures catering to our emotions again?

We shall see.

tra am 11. März 12

|

Permalink

|

0 Kommentare

|

kommentieren